Are we having fun with the lockdown yet? Some of you may live, like me, in a region where our pal COVID-19 seems to be under control—or you may be trapped in some dire realm where it is not. Yet, for even those of us who are momentarily spared, respite may prove temporary—it’s always best to stay safe and plan for the possibility of continued isolation. That suggests that it would be prudent to add to your personal Mount Tsundoku, preferably with tomes weighty enough to keep one occupied through weeks of isolation and tedium. Omnibuses could be the very thing! Below are five examples…

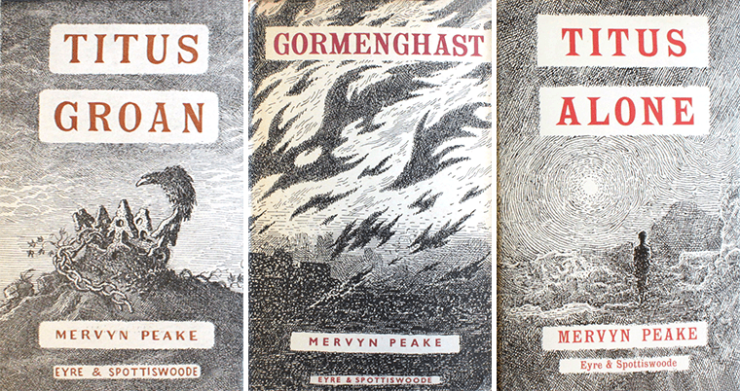

Mervyn Peake’s The Gormenghast Trilogy: Titus Groan (1946), Gormenghast (1950), and Titus Alone (1959)

Life in 2020 may be a bit dour, but not as dour as poor Titus Groan’s existence. Born into an aristocratic family with a lineage seemingly focused on breeding for eccentricity, Titus is raised in sprawling Castle Gormenghast, a grand gothic edifice as imposing as it is poorly maintained. The questionably sane inhabitants of Gormenghast sleepwalk though lives obsessed with tradition and rank. Titus, therefore, has a childhood that is both claustrophobic and soul-crushing. The arrangement has the tradition of centuries behind it, and little reason to expect that it will continue as it was. As events prove, it is as delicate as spun sugar. It only takes one manipulative villain to send Castle Gormenghast’s fragile society towards what is almost certainly a merciful collapse, and propel Titus towards escape into an unfamiliar world.

***

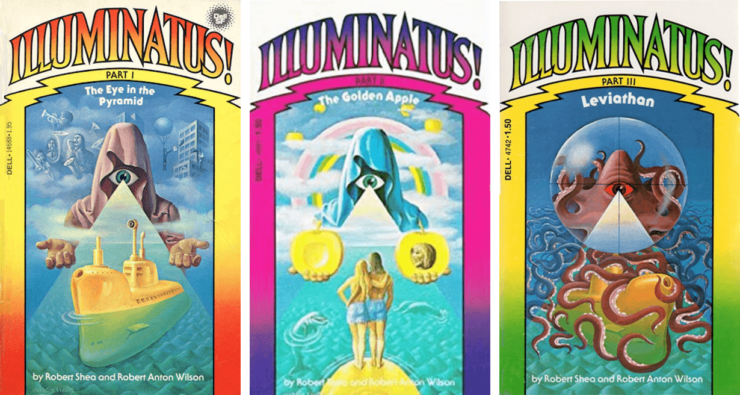

Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s The Illuminatus! Trilogy: The Eye in the Pyramid (1975), The Golden Apple (1975), and Leviathan (1975)

Inspired by a never-ending flood of paranoiac letters dispatched to the pair’s employer (Playboy), Shea and Wilson wrote a novel in which all conspiracies, even the contradictory ones, were true. It begins conventionally enough. New York Detectives Saul Goodman and Barney Muldoon investigate the bombing of a left-wing magazine; they’re also searching for missing editor Joe Malik. What would, in a better world, have been a simple case of domestic terrorism drags the two cops, plus the rest of the series’ vast cast, into a bewildering occult maze of plots on which the very fate of the world may depend. The trilogy is, to quote an old review of mine, “if drugs, sex, the occult, polyester, Studio 54, post-Watergate America, and the Playboy letters page were to have a monstrous baby.”

(Once again, I have rediscovered that there was a lavish stage version of the Illuminatus! Trilogy. I am, yet again, boggled)

***

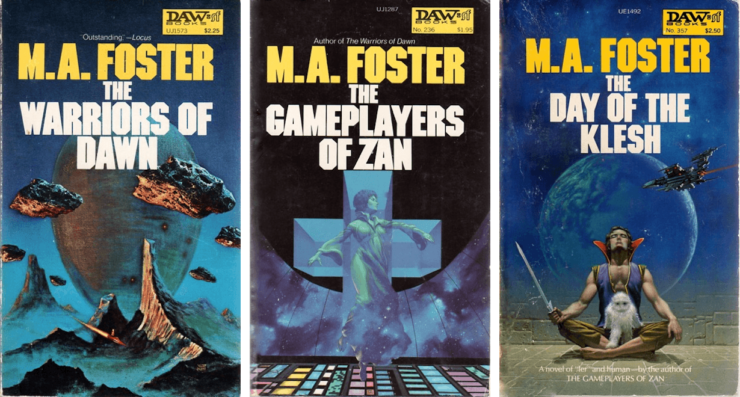

M.A. Foster’s The Book of the Ler: The Warriors of Dawn (1975), The Gameplayers of Zan (1977), The Day of the Klesh (1979)

Unlike the previous two examples, the Ler books are linked not by an ongoing plot but by a shared setting. Also, unusually, they were written out of internal chronological order. The genetically engineered Ler are a second human species, intriguingly different from baseline humans, but not at all the superhumans that researchers had intended. Although all three of the novels have their strong points, the gem is Gameplayers, chronologically the earliest, and the one that explores Ler society in most detail. The Ler, confined to a reservation in an overcrowded 26th century Earth, chafe against the restrictions required if they are to coexist with their far more numerous cousins. Cheap spaceflight is still a pipe dream, so accommodating the humans is a must for the Ler. All this is placed in jeopardy when a Ler woman gets caught robbing a museum, raising questions that the Ler would much prefer not to have been asked…

***

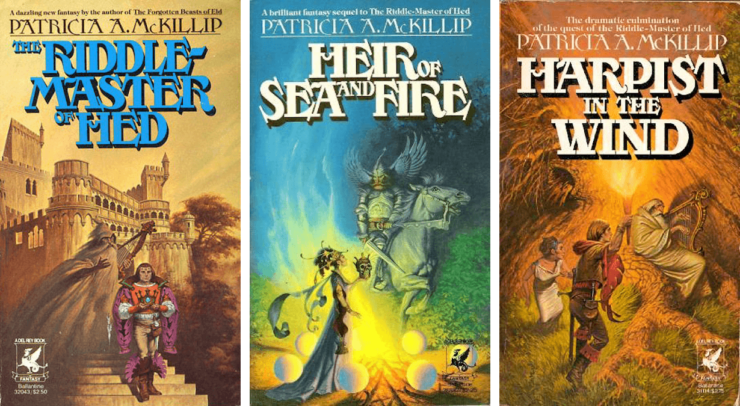

Patricia A. McKillip’s Riddle-Master Trilogy: The Riddle-Master of Hed (1976), Heir of Sea and Fire (1977), and Harpist in the Wind (1979)

Prince Morgon of Hed is a curiosity: a prince with ambitions above his station. The small and poor principality of Hed would be best served by a prince who’s willing to help out on the farm and haggle in the market. Would-be scholars like Morgon aren’t at all a good fit…but there he is, the prince. Morgon’s intellectual prowess wins him a spectre’s crown (which he keeps under his bed) and—quite unexpectedly—the hand of Raederle, second-fairest woman in the land.

It also drags Morgon and his loved ones into a grim struggle against a conspiracy of shapeshifters allied with the grand villain Ghisteslwchlohm. Sitting back and doing nothing means death. Survival means Morgon and Raederle must accept transformation beyond recognition. An enticing tale made even more remarkable by McKillip’s luminous prose.

***

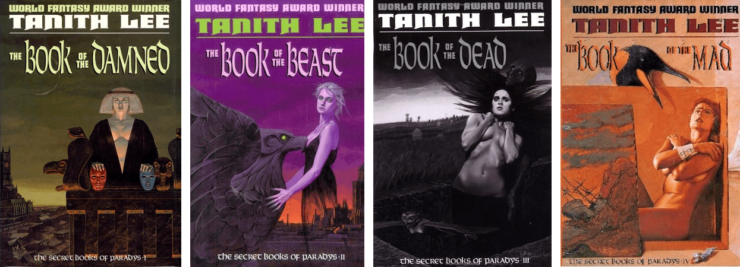

Tanith Lee’s The Secret Books of Paradys: The Book of the Damned (1988), The Book of the Beast (1988), The Book of the Dead (1991), and The Book of the Mad (1993)

Paradys is far across the Uchronic seas from our own city of Paris. Paradys is that world’s City of Lights: It’s cultured, cosmopolitan, and decadent, but it’s not a paradise (as its name might suggest). It is an ancient city filled with answers to questions no sensible person should ever ask. Some inhabitants are monsters who deserve whatever hard fates come their way, but most are unfortunates in a society run for the benefit of the debauched and wellborn. Sometimes they can only escape into madness or death. Which is to say, no matter how grim things seem to you now, your sufferings are probably lighter than those afflicting Jehane, Oberand, Hilde, and the other characters in these books.

***

Looking at my selections, I note that they tend toward the dour and challenging. I’ll have to come up with another essay, to serve as a unicorn chaser. In the meantime, please share any book-related thoughts and suggestions in the comments…

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is currently a finalist for the 2020 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.